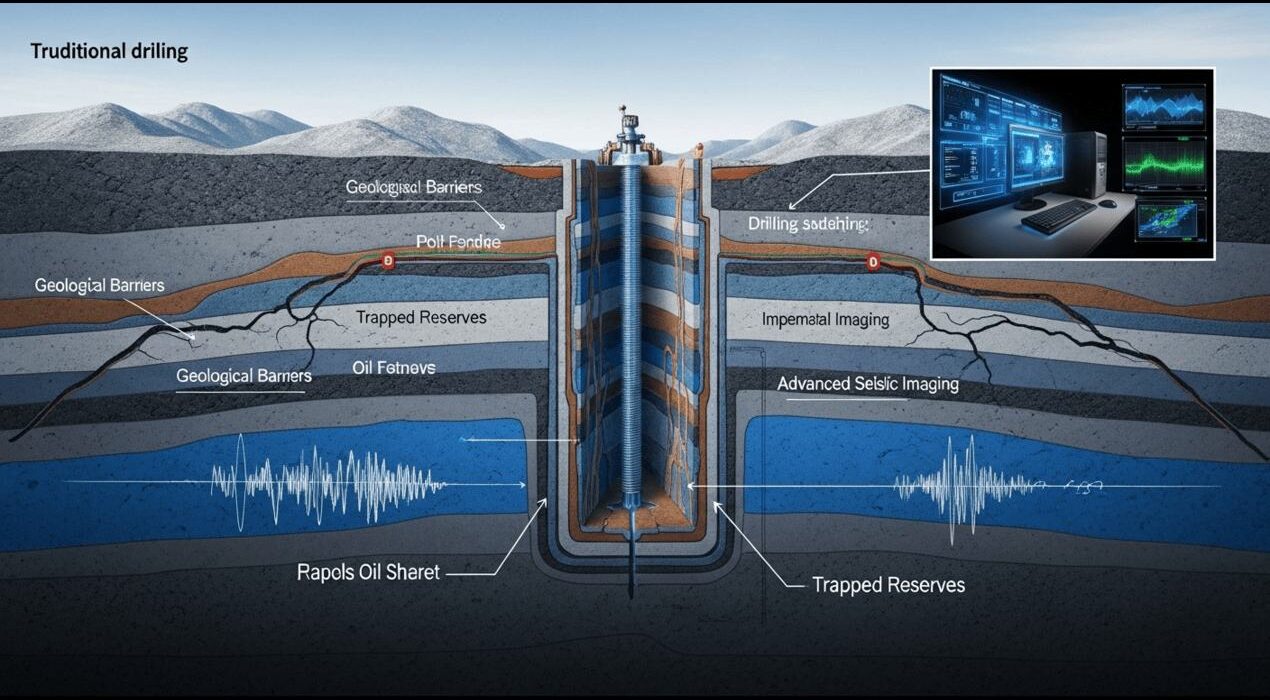

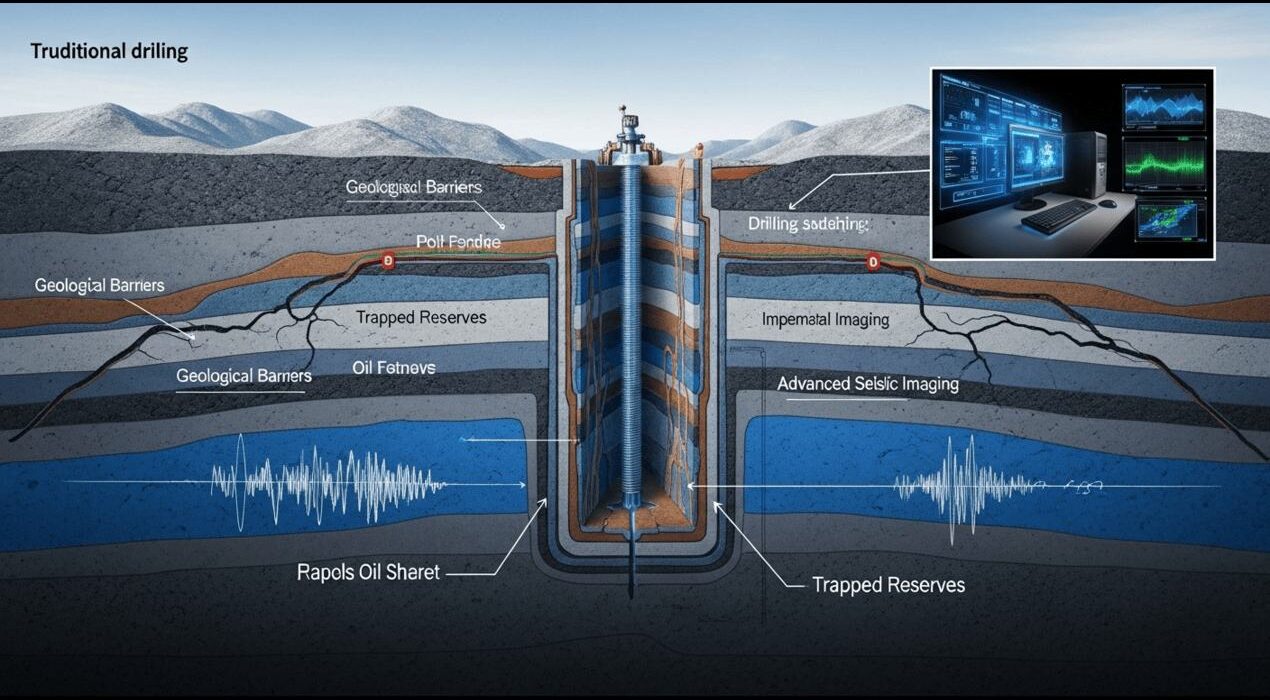

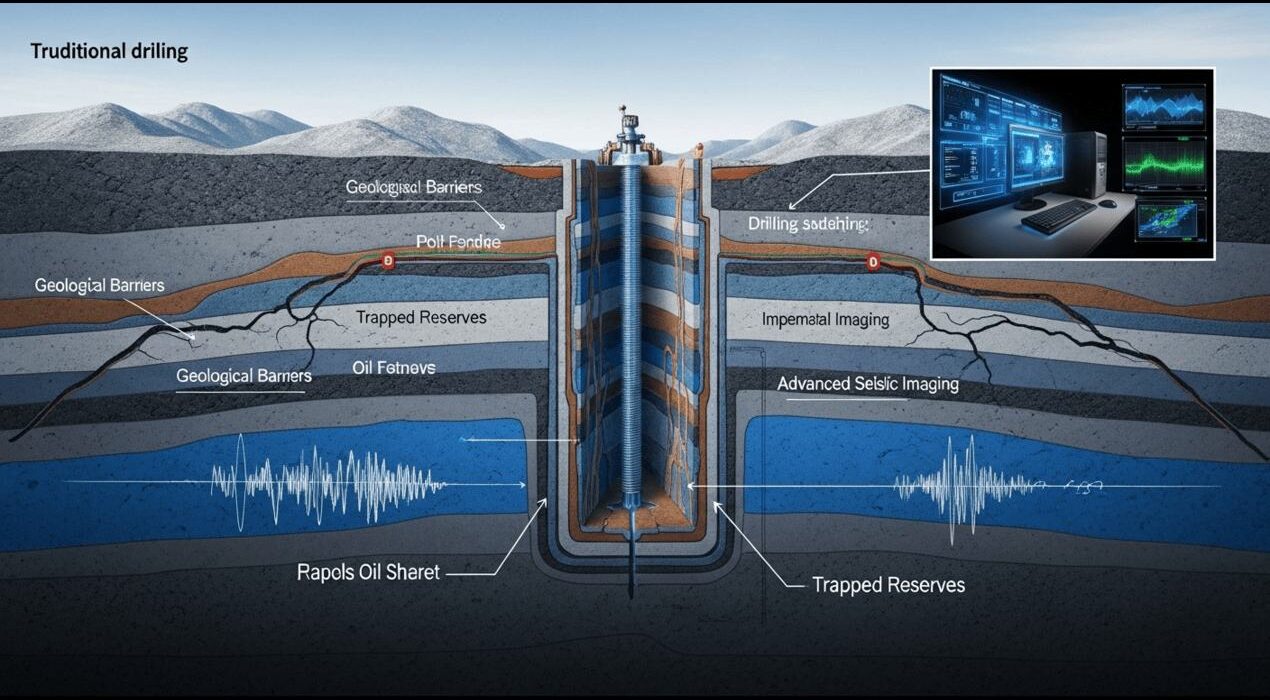

Oil wells that appear “dry” may not actually be empty. A research team from Penn State University, using PSC’s Bridges-2 supercomputer, discovered that hidden geological structures can block oil flow, leaving untapped reserves behind. Their work could revolutionize drilling methods by helping companies recover resources once thought lost.

Traditionally, seismic imaging has been used to estimate the size of oil reserves. This technique works much like ultrasound, mapping underground rock by the way sound waves travel through it. While effective, wells often run dry sooner than expected. “They started drilling in 2008 and … based on their estimation … they could produce oil for 20 years, 30 years. But unfortunately, after two years, there was nothing,” explained Penn State’s Tieyuan Zhu.

To solve this mystery, Zhu’s team added a time component—turning 3D seismic scans into 4D animations—and measured not just how long sound waves took to travel, but also how their amplitude was dampened by oil. This revealed hidden rock barriers within reserves, undetectable with older methods, that prevented oil from reaching wells.

The breakthrough was made possible with PSC’s Bridges-2 system, which provided the immense computing power and memory needed to process massive seismic datasets. By combining time-lapse imaging with expanded data analysis, researchers showed that seemingly depleted wells may still hold significant oil.

In some cases, the fix was straightforward: drilling slightly deeper could access the trapped reserves. Reported in Geophysics, the findings are now being scaled up to cover much larger oil fields. This approach could reduce waste, improve efficiency, and make extraction cleaner by avoiding unnecessary drilling.