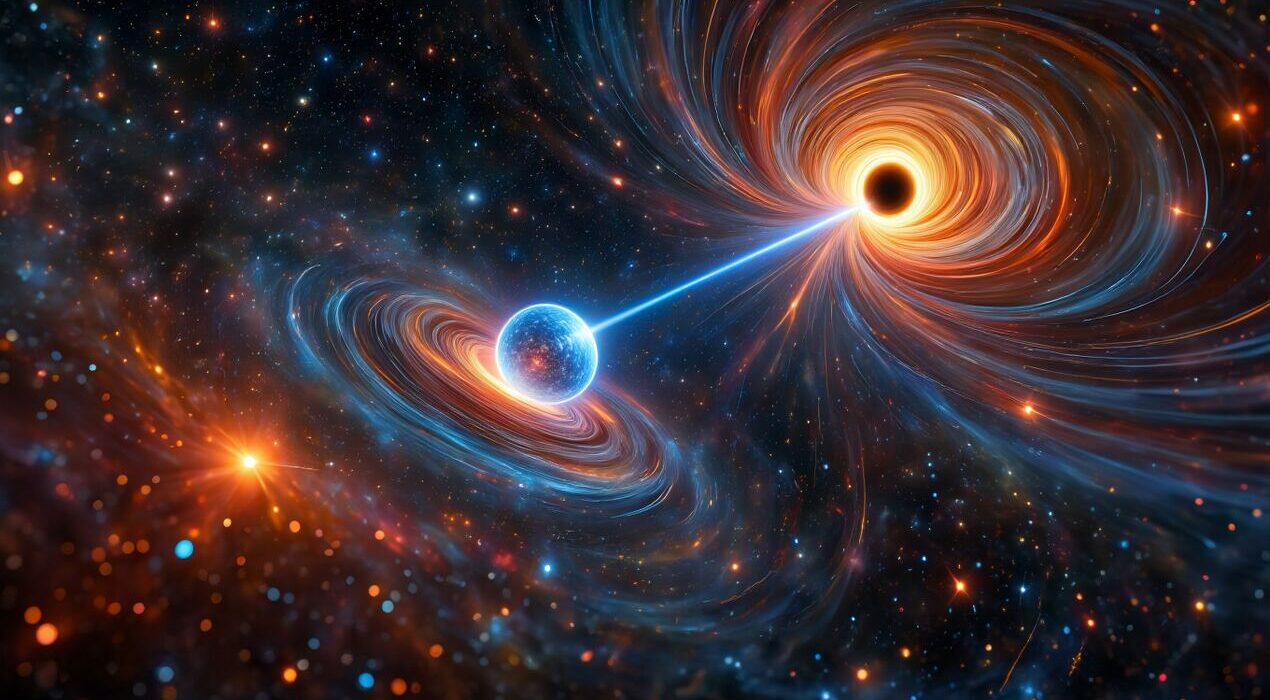

Ultra-Fast Pulsar Found Near Milky Way’s Supermassive Black Hole

Scientists scanning the heart of our galaxy have found something incredible. They detected a possible ultra-fast pulsar near the supermassive black hole at the Milky Way’s center. This cosmic object spins every 8.19 milliseconds. That means it rotates about 122 times per second. Researchers from Columbia University made this discovery. They worked with Breakthrough Listen, a project searching for signs of life beyond Earth. The team published their findings in The Astrophysical Journal.

What Exactly Is a Pulsar?

Pulsars are the dead cores of massive stars. These dense remnants, called neutron stars, spin rapidly. They generate intense magnetic fields as they rotate. This creates focused beams of radio waves. These beams sweep across space like lighthouse lights. When undisturbed, pulsars emit radio pulses with remarkable consistency. Therefore, they function like incredibly precise cosmic clocks. Millisecond pulsars spin especially fast. As a result, their timing behavior becomes even more stable.

Why This Discovery Matters

The pulsar candidate sits close to Sagittarius A*. This is the supermassive black hole at our galaxy’s core. It contains about 4 million times the mass of our Sun. If astronomers confirm this object, it could open new scientific doors. Tracking a pulsar near a black hole would allow precise measurements of space-time. Scientists could test Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity under extreme conditions. “The gravitational pull of a massive object introduces anomalies in pulse arrivals,” explains Slavko Bogdanov from Columbia Astrophysics Laboratory. “Pulses traveling near massive objects may also experience time delays. This happens because massive objects warp space-time.”

How Gravity Affects Pulsar Signals

Einstein predicted that massive objects bend space and time. A pulsar orbiting near a black hole would prove this dramatically. Its signals would travel through distorted space-time. Scientists could measure these distortions precisely. This would provide the best test yet of General Relativity.