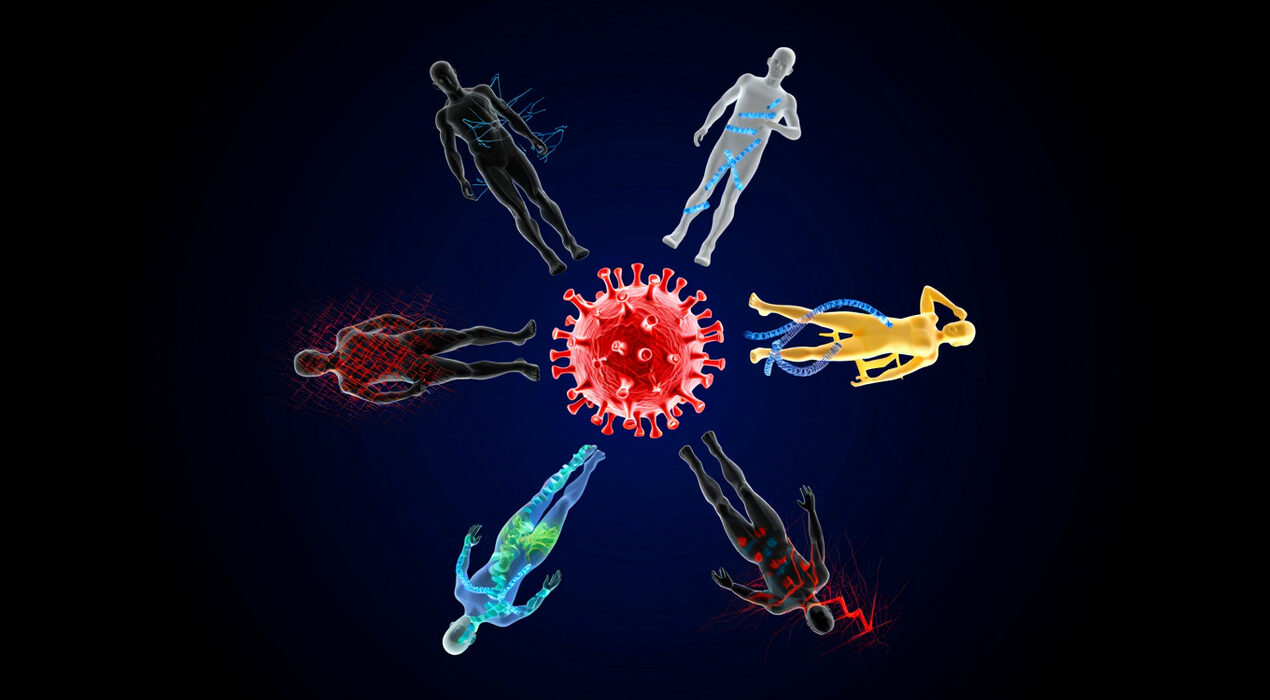

Why the Same Virus Hits People So Differently, Study Finds

The COVID-19 pandemic made this mystery impossible to ignore. Scientists now have a clearer answer. It comes down to two key factors. Your genetics and your life experiences shape your immune system. Both leave lasting molecular marks on your cells. These marks determine how you fight infections.

The Hidden Answer in Your Cells

Every cell contains your DNA. However, not all genes are active. Small chemical tags called epigenetics turn genes on or off. Unlike your DNA sequence, these tags can change over time. Life experiences like infections and vaccines leave epigenetic fingerprints. As a result, your immune cells carry a record of your personal history.

What the Salk Team Discovered

Researchers at the Salk Institute studied blood samples from 110 people. These individuals had diverse backgrounds and exposure histories. Some had fought flu, HIV, or COVID-19. Others had received vaccines or encountered pesticides. The team examined four major immune cell types. T cells and B cells provide long-term memory. Monocytes and natural killer cells respond quickly to threats. They created a detailed catalog of epigenetic markers. This helped separate genetic influences from life experiences.

Key Discovery: Nature vs. Nurture in Immunity

The findings were striking. Genetically influenced changes clustered near stable gene regions. These were especially common in long-lived T and B cells. In contrast, experience-driven changes concentrated in flexible regulatory areas. These regions help control specific immune responses. Inherited genetics establishes stable, long-term immune programs. Life experiences fine-tune adaptable, context-specific responses. Both forces work together but in different ways.

The Future of Personalized Treatment

Senior author Joseph Ecker explains the vision. Our immune cells carry molecular records of both genes and life experiences. By resolving these effects cell by cell, we connect risk factors to where disease begins. This work lays the foundation for precision prevention strategies. For COVID-19, flu, or future pandemics, we may predict outcomes even before exposure. The study published in Nature Genetics on January 27, 2026. It offers hope for more targeted, effective treatments tailored to each person’s unique immune history.